Blogs

The Making of Technique in the Arts: Concepts and Practice from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century

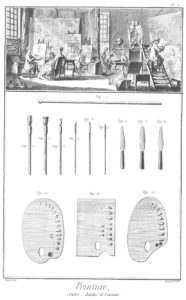

“Peintures en huile, en miniature et encaustique,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 8 (plates) (Paris, 1771). Plate I: Painting, Atelier, Paint Pallet and Brushes.

The terms ‘technique’ and ‘technical’ are used widely in relation to art, art history and science today, both to refer to the technical analysis of artworks and to a more holistic analysis of creative processes. Yet we do not have a history of the shifting meanings of the term ‘technique’ in the arts and sciences. The word ‘technique’ was a neologism in the vernacular, and started to appear in treatises on arts and sciences from the middle of the eighteenth century. Rooted in the Greek techne, which was translated routinely as ‘art’ until the mid-eighteenth century, technique referred to processes of making or doing and their products. Such processes had been described to previously as ‘art’, ‘methods’, ‘manners’ or ‘mechanics’ in the vernacular, and they were recorded in text with the intention of documenting and/or transmitting practical skills and knowledge.

On 26 and 27 October, Sven Dupré and I are hosting an international workshop at Utrecht University with the aim of bridging the gap between the changing concept of technique and the practices currently described by it. Questions we seek to answer are for example: how was what we now call ‘technique’ in the arts and sciences described and understood before the term took hold? More specifically, how were techniques in the arts described between 1500 and 1900? What kind of written sources can we distinguish, which terms were used to describe and instruct technique in various languages, and who were the intended audiences of these works?

Hans-Jörg Rheinberger will give a public keynote lecture, entitled “The Hands of the Engraver – Albert Flocon meets Gaston Bachelard”

Moreover, we will look at the linguistic history of technique in the arts, with questions such as why the term ‘technique’ first emerged around 1750, and what did it mean initially to artists, art theorists, and natural philosophers? Is there a connection with the emergence of categories such as aesthetics, fine art, craft, mechanics, and technology? Did the meaning of ‘technique’ and related concepts vary between periods, practices, and European languages, and how can we use data and concept mining to understand this? What do we mean by ‘technique’ in relation to art now, and can we use the same word to describe historical knowledge and practices?

Another issue closely related to the understanding of the concept of ‘technique’ in the arts is the development of so-called somatic language. Somatic language to describe measurements and sensory characteristics of materials traditionally played an important role in technical art texts, but seems to become rarer or more standardized over time. This kind of language guides the reader’s posture, as well as the use of their own body, and tools and materials, yet it is often unspecific and metaphorical (‘shift your weight’, ‘a handful’, ‘like yoghurt’), and meanings and interpretation can vary wildly in different languages, times, and cultures. How did the use of this kind of somatic language change in Europe between 1500 and 1950? What was the influence of standardization on conservation practices?

During the workshop, we will discuss these and related questions in panels of specialists from a variety of fields, such as history, art history, intellectual history, philosophy, and linguistics. Each interdisciplinary panel will focus on a particular concept, but there will also be ample time for exchange between the various panels.

Limited seating is available, please contact j.briggeman@uu.nl if you are interested in attending.