Blogs

Choreographies of Glassmaking: An Impression

By Márcia Vilarigues

For those of us who have watched master glass makers working in their studio, it is impossible not to be enchanted by the choreography that unfolds in front of us, where glass blowers move in perfect balance and synchronisation. An intimate relationship evolves between artist and material. This scenario is replicated at the Research Unit VICARTE – Glass and Ceramic for the Arts, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. We collaborate with Artechne’s Thijs Hagendijk and Sven Dupré to explore this relationship, and how it connects to the orchestrated composition of recipes and instructions for glassmaking, through recipes from Johannes Kunckel’s 1679 Ars Vitraria experimentalis.

When concentrating on the re-working of the web of recipes, annotations and comments for the production of rosichiero (clear or transparent red) glass and enamels, several choreographies between makers, scientists, materials and texts, past and present, take place [1]. The work includes the production of each individual compound of the recipes following Kunckel’s instructions until the production of the final glass. We start with the first challenge: to transform these historical texts into step-by-step protocols for chemical synthesis. We deconstruct and reconstruct those sets of instructions; raw materials and measurements are identified, each process described in the recipes is interpreted, voids are filled with our own experience. We move between pages and languages (German, Italian, English, Dutch, Portuguese), while embracing many diverse strands of expertise (glass science, history, chemistry, conservation), surpassing jargons, methods of speaking, diverse backgrounds; finding a common language. While working we weave our own web of knowledge and experiences.

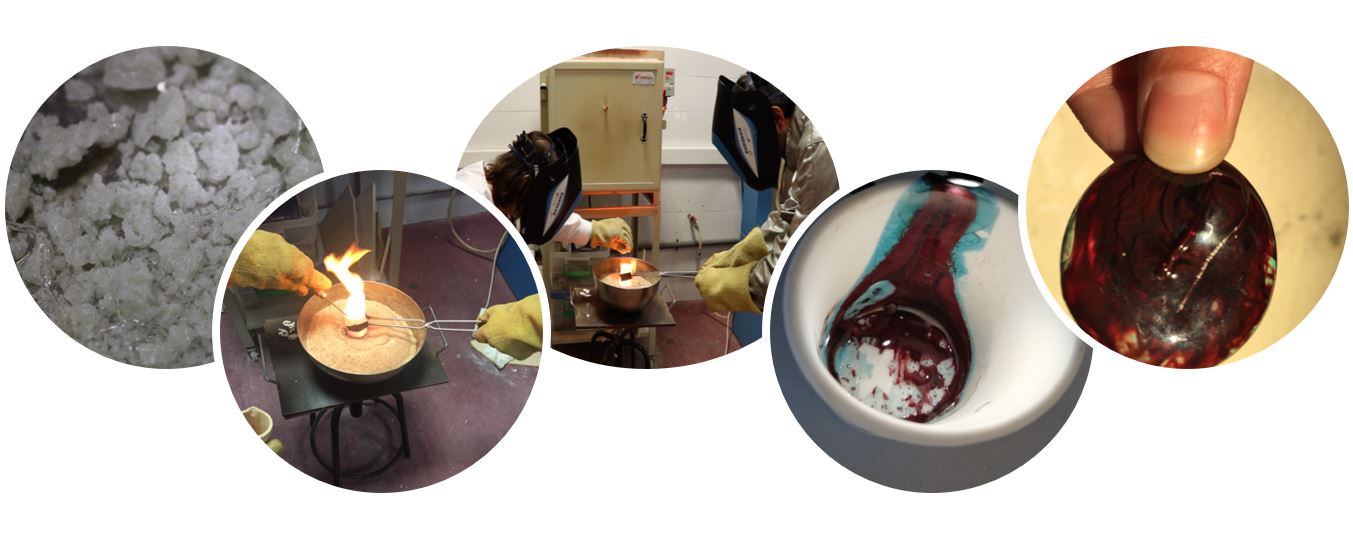

Following recipe 125 (Eine andere Roſen farbichte Smalte oder Schmeltzglas zum Gold); the first step sends us to recipe 124 (Eine Roſen-farbichte Smalte oder Schmeltzglaß zu machen/ von den Jtaliaͤnern Roſichiero genandt/ mit welchen das Gold bemahlet wird), which includes the way to produce a crystal glass (Fritta Cryſtalli, a clear glass). Here we face the first limitation: We don’t have in our laboratory Levantine ashes or Tarsus powder (no present ones are equal to those collected in the past), and choices have to be made on how to mimic these raw materials. The second step demands the preparation of ashes of lead and tin, for which we have to go back to recipe 93 (Die Materia/ aus welcher alle Schmeltzglaͤſer oder Smalten bereitet werden.). For this recipe, as for all recipes on how to produce glass, only the best products should be used (des beſten Bleyes (…) und des beſten Zinns). We mix and melt the two ingredients, add minium and mix, add calcined copper (a step not described in any recipe by Kunckel) and cream-of-tartar (from wine lees), mix again. Each time this process involves a choreography performed at 1200 ºC. One person opens the furnace and takes out the crucible, another adds and mixes the different elements in the glass melt. The crucible is then returned to the furnace in a tantalising balance. The final step is also a revelation: will we obtain the desired colour (or what we envisage it should be)?

This endeavour is a work-in-progress, the re-working of historical processes and experiences raises countless questions and allows us to witness the importance of the experimental attitude of the ‘composers’ of glass. Each explored recipe reveals the interconnectedness between the fire technologies, the need for common elements as raw materials, high temperature furnaces, crucibles, and demands the sharing of knowledge of technology and materials. We further seek to relate the choice of raw materials and production techniques to historical developments in science and technology, especially Kunckel’s work in chymistry. The discovery of purification methods, new elements and chemical synthesis not only enabled the production of higher quality glass, but also resulted in the emergence of new colours, new varieties of rosichiero.

At the end of the day this is about ‘how persons make things and things make persons’ ([2] Tilley et al., 2013) – both now and in the past.

[1] ‘choreographies’ here is an actor’s category: it is the term that glass makers use to describe their shared operational sequence. [2] Chris Tilley, Webb Keane, Susanne Kuechler, Mike Rowlands, Patricia Spyer (eds.) (2013), Handbook of Material Culture (Sage Publications).