Blogs

Exploring Historical Blacks: The Burgundian Black Collaboratory

*This blog was cross-posted on the website of Refashioning the Renaissance Project (ERC) on 21/02/2019*

By Paula Hohti

In January, I participated in a workshop on historical black dyes in the Netherlands, titled ‘Burgundian Black Collaboratory‘, co-organised by Jenny Boulboullè from the ERC ARTECHNE research group and Claudy Jongstra—a talented and creative textile artist working on historical wool fibres and natural dyes—in collaboration with Natalia Ortega-Saez, and the Museum Hof van Busleyden. Led by Jenny and hosted by Claudy on her farm in Hùns, I and the rest of the group spent three days in a green house in the Dutch countryside, trying out recipes and testing how ‘a perfect Burgundian black’, once seen as the utmost civic and professional colour, could be created by using historical dye recipes. The aim of the workshop was to provide material for the planned exhibition at the Museum Hof van Busleyden, and an e-book project, edited by Jenny Boulboullé and Sven Dupré.

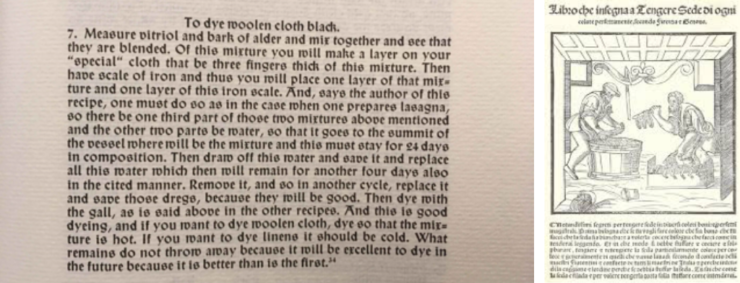

Black is the most difficult colour to dye, because it washes out easily and degrades faster than other colours. Given the complexity and expense related to dyeing black, historical recipe books are full of black dye recipes, from simple and cheap procedures that could be applied by men and women at home to complex and expensive recipes that required professional skill and economic capital. In the ‘Burgundian Black Collaboratory’, we worked in groups to test these recipes, using Flemish and Italian sources, including the Venetian Plichto by Rosetti (1548), which is the first known book of dye recipes intended for professional dyers. This allowed us both to explore the process and methodology of reconstructing historical recipes (the recipes are vague and rarely include accurate measures!) as well as to evaluate how well the original recipe might have worked in terms of creating black.

Black was traditionally produced from barks and roots that contain tannins (such as alder, walnut and chestnut). To provide a colour that stayed longer, dyers started combining tannins with iron salts that acted as a mordant. This produced a more beautiful black, but the result was corrosive to the fabric.

A better -but much more expensive and complicated – way to achieve black colour was to use a madder and woad base overdyed with tannins such as gall nuts. By the late sixteenth century, the best-known method to get a beautiful, deep black was to dip the silk or wool first in either a woad or indigo bath that gave the cloth a beautiful blue undertone, and then, when the fabric was dry, to overdye the fabric with madder (red dye) on an alum mordant.

The challenges of reconstruction, and the great differences between recipes of black, became well visualized and materialised in the results. Some did not turn black at all, others were initially black but turned brown overnight when they were dry, while others were just beautifully deep black. These differences were due to the fact that some recipes did not provide as precise instructions as others, they were misleading, or they simply did not work.

The fascination and interest of dyers over black reflects the fact that black was an ultimate colour of power, status and fashion in early modern Europe. By the end of sixteenth century, it was essential for young men of wealthy families to have their portraits painted in black. Although deep, sumptuous blacks with blue, purple or red undertones are usually associated only with the elites and merchant classes, black was, in fact, the most important colour also in clothing of our ordinary artisans and shopkeepers. Our initial data shows that, for example in Siena between 1550–1650, whenever colour was mentioned, 25% of all male and female clothing consisted of garments dyed with different types of blacks, including jackets, breeches, over-gowns among others.

Recipes for dyeing black, intended for domestic use by ordinary people, were available also for our artisan groups through cheap printed pamphlets and booklets that were sold at a cheap price by, for example, street peddlers. One of the recurring recipes for home-based black dyeing, described ‘for women after they have spun their yarn’, was prepared by boiling oak gall with a small amount of copper sulphate and Arabic gum -the latter which was added to give the black a degree of lustre. While this might have produced a reasonably beautiful black colour, the copper made the woollen yarn weak. For this reason, professional wool dyers, at least in Venice, were forbidden by their guild to use this method.

We will be experimenting with the Refashioning the Renaissance team with domestic dyeing and colour, and investigating what kinds of blacks among other colours our artisans wore, what these looked like and how durable these were. Please keep an eye on Michele Robinson’s talk and article on how to use printed sources as evidence for the history of lower-class dress, on Sophie Pitmans dye experiment during our trip to Colombia University’s Making and Knowing Project, and my forthcoming articles on Colour, on red dyes, and the social and culture meanings of black in sixteenth and seventeenth century European fashions.

Literature

Susan Kay-Williams, The Story of Colour in Textiles: Imperial Purple to Denim Blue (Bloomsbury, 2013).

Natalia Ortega Saez, Black Dyed wool in North Western Europe 1680- 1850: The Relationship between Historical Recipes and the Current state of Preservation (unpublished PhD. Dissertation submitted for University of Antwerpen, 2018).

Dominique Cardon, Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science (Archetype Publications, 2003).

Elizabeth Currie, Fashion and Masculinity in Renaissance Florence (Bloomsbury, 2016).

Riikka Räisänenm Anja Primetta, Kirsi Niinimäki, Luonnonväriaineet (Maahenki 2015).