TAH interview Jørgen Wadum, Keeper of Conservation at the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen

What are the most important research questions being asked in TAH?

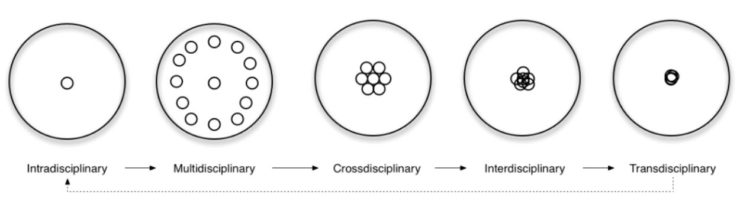

In my view a technical art historian is someone who by means of sophisticated thinking and a vast array of the research tools currently available engages in the understanding of the making and meaning of our past and present cultural heritage. A technical art historian knows the benefits and limitations of technical examination, without necessarily being able to operate the specific scientific machinery themselves. The person is able to engage with a cross- or interdisciplinary dialogue, asking relevant questions within the discourse. One issue challenging TAH, apart from the necessity of functioning across different research cultures, is that the field is able to find its niche of operation. The importance of the proposed research questions must be recognized, questions which examine and reveal the interactions of material availability and artistic creativity. For TAH to expand it must therefore actively participate in digital research infrastructures, or instigate new modes of operation. The sharing of big data and the offering of free transnational access to metadata on analogue resources is paramount.

Do you consider technical art history a sub-field of art history?

One of my colleagues is a conservation scientist, and he would claim that he is also a technical art historian, as he uses advanced scientific equipment and a variety of primary sources in his research into the making of objects. What he does is based on the natural sciences and could not have been performed by people educated in the humanities alone. So again the ‘disciplinarities’ come into the picture.

I believe that an answer to the question could be a collaboration between the conservator, the conservation scientist and the (art-)historian, often described as the ‘three-legged stool’ of heritage research, offering the best insight into objects in our cultural heritage.

Is TAH is ‘an enhanced and more scientific’ connoisseurship?

Some months ago I listened to a talk by Martin Kemp, Emeritus Research Professor in the History of Art at Oxford University, where he explained that “a truism is that the item must be inspected closely in the original before putting forward or dismissing an attribution. This comprises the basis of traditional connoisseurship—or what I prefer to call judgment by eye. It is valid, but only to a limited degree. There are two major qualifications to the truism, both arising from modern technologies of imaging. The first is that images with a very high resolution produced under ideal lighting or by multi-spectral scanning may well disclose more than obtained by first-hand inspection, even aided by magnification. The second is that varieties of scientific analysis may produce clear evidence about the origins of the work, most definitely to exclude the artist or period or place from which the work is supposed to originate.” [1]

Referring to ‘the trained eye,’ I agree that this could be that of an art historian, but this could also be that of a conservator or scientist, knowing where and when to draw on another discipline in order to reach a well-argued conclusion. In other words, traditional connoisseurship is being confronted with new scientific technology that can often legitimately offer new insights. However, there will also be those who will claim that TAH is what art history always was about before it divested itself of the object and became ‘New Art History’ (first discussed under this name almost forty years ago) taking attention away from the works themselves and turning them into simple messengers or intermediaries. For the technical art historian, the material in the object itself matters, in terms of its impact and manipulation. Engaging with those partners I previously termed the ‘three-legged stool’ in collaborative research is here beneficial—whether through direct collaboration or through sharing data held by infrastructures. Although we refer to the term TAH as a more recent invention, it may be worth remembering the initiatives behind the founding of the the Rathgen-Forschungslabor, a leading institute for conservation science, art technology and archaeometry at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, which was founded in 1888 as the Chemischen Labors der Königlichen Museen and is the oldest museum laboratory in world. It was founded on questions of material authenticity and the advanced examination of art objects—precisely the domain of the technical art historian.

What do you see as the major challenges in TAH education?

We have so far only little experience on which to base our identification of challenges in TAH education. Did the technical art historian of the past emerge from an interest in objects, and through the keeping of a collection also train in technical analysis, as took place at the research institutes that emerged throughout the world over the twentieth century? Students of art history may have been trained in the use of infrared reflectography since the 1970s, while scientists brought their analytical results to discussions between the disciplines. During the 1980s and 1990s, conservators began to play a more significant role in technical art history by employing their well-trained skills to investigate objects, their materiality and deterioration—the latter often significant in explaining the change that an object’s appearance may have undergone, affecting its interpretation—something not always obvious to the non-professional conservator.

Nowadays TAH is being offered as a one-year MA program in Glasgow, and has been running successfully for a number of years. At the University of Amsterdam a two year MA in TAH will be offered from September 2015, and in Stockholm courses in TAH will be available at the University from September 2015. One issue to remain aware of however is to be sure the students are trained in a way that is conscious of the ‘disciplinarities’ approach, in order to offer them ample opportunities for collaboration after their graduation. The idea of New Art History, where the actual works of art are overshadowed by their abstract meanings and connotations may have come to a close. As a result of this belittling of the object—taking attention away from the works themselves and turning them into simple messengers or intermediaries—a new ‘material turn’ has recently begun to take shape.[2]

This development is a change from ‘Old Art History,’ which was very much about individual thinking and producing theories developed in solitude. This may function almost as a counterpart to the natural sciences, where teams could produce scientific facts from the very same objects that were the subject of entirely different conclusions. It is in this minefield between different breeds, where each must master alien languages and approaches, that we find the technical art historian. That will be one of the hardships of the future, to create people that are receptive to other disciplines, however difficult and different their approaches may be.

[1] Quote from Martin Kemp’s This and That- anything and everything, from the standpoint of a historian of visual things: “Michelangelo” bronzes and judgement by eye”, Sunday, 8 February 2015. http://martinkempsthisandthat.blogspot.dk/ [2] Kristina Jõekalda (2013) ‚What has become of the New Art History?‘, from https://arthistoriography.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/jc3b5ekalda.pdf