Blogs

The Role of Print Production in the Circulation of Anatomical Knowledge

By Alice Zamboni

Since January 2019, I have been conducting research for my PhD at Utrecht University. I am hosted by the Artechne group, whose interdisciplinary work and employment of empirical approaches to art history is offering much intellectual stimulation for the development of my thesis. My PhD project examines the role of print production in the circulation of anatomical knowledge. My aim is to investigate the visualisation of the human body from the perspective of artists and physicians in the 17th-century Netherlands. I am particularly interested in pedagogic manuals and books illustrated with engravings or etchings that were used and read by art and medical practitioners: two communities of knowledge with distinctive aims and professional affiliations, but also a shared interest in human anatomy.

In 17th-century art treatises, writers from Jacob van der Gracht through to Willem Goeree and Gerard de Lairesse emphasised the fundamental relevance of anatomical knowledge within the artist’s training. In the year in which he joined the Painters’ Guild in Haarlem, Dutch artist Casper Casteleyn also produced a charcoal drawing in which an eerily animated flayed body (écorché) sits at the very centre of his composition amidst a small crowd of onlookers. Whether their bodies are youthful and energetic, or frail and decaying, clothed or nude, for this artist the human figures all shared a connection to the écorché , in that knowledge of the body’s inner workings was deemed essential to depict a proportioned and harmonious human form.

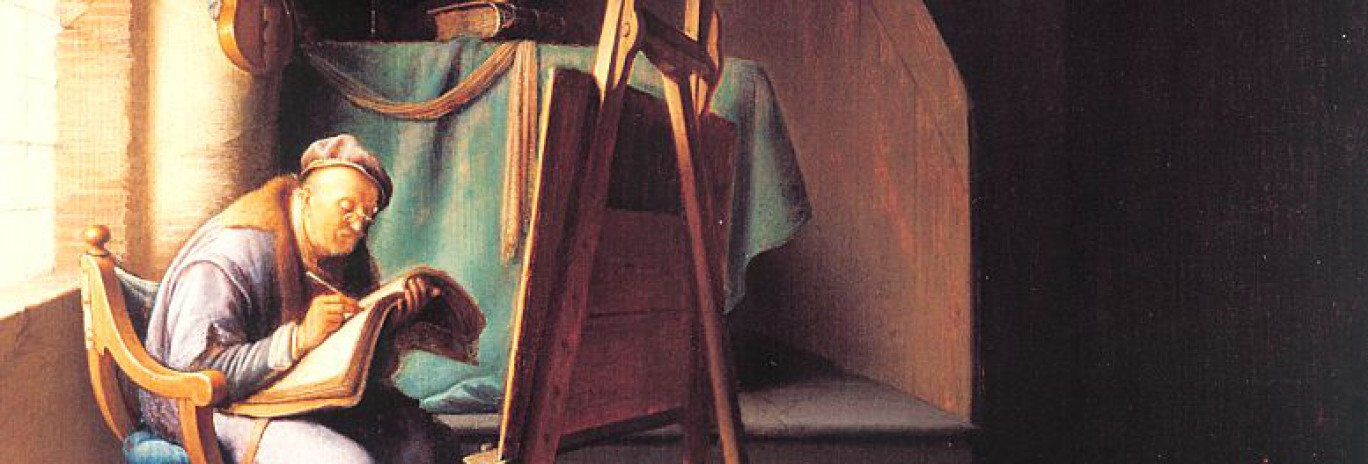

Casper Casteleyn, Title page design with anatomical studies, 1653. Black chalk and brush in grey, 33 x 20.9 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Notwithstanding the centrality ascribed to anatomy in the artist’s curriculum, we know relatively little about the practical ways in which art practitioners gained knowledge of human anatomy. Compared to the 16th century, for instance, I find there is less collaboration between art and medical practitioners towards the production of lavishly illustrated atlases. Equally, public anatomy lessons that artists could attend were fairly rare occurrences. Conversely, there is a proliferation of illustrated treatises and book of plates about the human body. That drawing by Casteleyn, for example, is believed to be a title page design for a series of now lost anatomical studies. This group of resources tailored to artists includes drawing manuals: volumes centred around the human figure, which are, however, rarely discussed in relation to the study of anatomy and its visualisation. At the same time, an increasing number of medical texts is used for didactic purposes and therefore complemented by engraved illustrations, which are the work of less skilled or still anonymous draftsmen and have received little art-historical consideration.

I have opted for a thematic approach to compare traditional medical illustration with drawing manuals and other illustrated resources addressing artists. Because the complex interrelationship between body and book is central to this project, one section is devoted to the analysis of visual resources that conceive the body as a text. A perfect example is Crispijn II de Passe’s drawing manual ‘t Licht der Teken en Schilderkonst (The Light of the Art of Drawing and Painting), Amsterdam: 1643. This folio book illustrated with engravings suggests the presence of analogies to the practice of writing in the instruction of art pupils wishing to learn how to draw the human figure. Across the pages, the human body is subjected to a visual dissection, with the limbs gradually reassembled just like the letters of an alphabet. A similar use of parallelisms with the practice of writing and reading also emerges in illustrated medical texts coeval to De Passe’s manual. These juxtapositions allow me to consider the multifaceted relation between the physical body and its representation. From the perspective of artists, it is interesting to think about what kind of knowledge they could gain from printed visualisations of the body when their ultimate scope was the depiction of a human figure endowed with lifelikeness.

Examining the circulation of anatomical knowledge is also making me think carefully about the materiality of illustrated books and their reception in the early modern Netherlands. Positing the category of the artist as a reader has encouraged me to look more closely into ownership of anatomy books: for instance, research into inventories and auction catalogues of their libraries has uncovered the presence of several specialist medical textbooks on artists’ shelves. Whilst in the Netherlands I am keen to examine more closely their making process of the books as material objects and conduct archival research that can deepen my understanding of the production, reuse and circulation of anatomical illustrations.

I had always intended to spend part of my time as a PhD candidate in the Netherlands, both to undertake further research in Dutch libraries and archives and to become acquainted with a new academic culture. Therefore, I am particularly grateful for the opportunity to spend these months hosted by Utrecht University’s Art History Department and the Artechne project. I am confident that by the end of this term through conversations with members of the group, attendance of the Colloquium in Technical Art History and of some art history classes I will have gained new insights into interdisciplinary research, the application of empirical methods to art history and teaching methods that promote hands-on learning.