Blogs

A Brief History of Making Copper Objects. Part 3: Hammering, Hot and Cold Work

* This text is based on an essay originally written for the MSc in Conservation, UCL *

By Mariana Pinto

As mentioned before, techniques used in the arts can leave traces in objects, and these may help us to understand the manufacturing process of an artwork. In the first entry, a short introduction of copper was provided, including the five steps for the smelting process of this metal. Since casting has already been discussed in the second entry, this third and last part will explain how hammering was carried out in ancient times, including some reflections on how to recognise such technique in manufactured objects.

Copper and its alloys are softer than other metals, so they can be hammered and stretched relatively easy. If the metal is hammered continuously, it becomes increasingly harder, but also more brittle; so if the treatment is not stopped in time, the metal will crack. The reason why this happens is because the hammering distorts the crystalline structure of the metal. If this happens for a long time, the structure deteriorates to the point where the crystals part. Therefore, the metal is annealed before it reaches this point. This means that the metal is heated and cooled down again, so a new crystalline structure is formed -although different from the original one- that will make the metal malleable again. If more cold work has to be done, the process of annealing may have to be repeated several times[1].

Minoan copper ingot from Zakros, Crete (Photo by Chris73, image from Wikimedia Commons) . File URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Minoan_copper_ingot_from_Zakros,_Crete.jpg

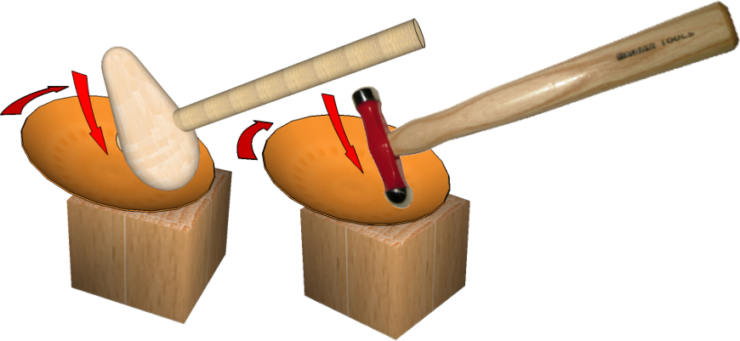

Hammering was used to make sheet bronze and bronze vessels. In the case of sheet bronze, the worker began with an ingot which was flattened by hammering, using stone pebbles of different sizes as tools for this process (image 1). Such product could be used, for instance, as cladding for wooden objects. On the contrary, bronze vessels were more complex to manufacture, and one of two different techniques was used, or even a combination of both of them. The first technique is called hollowing (image 2): the vessel was made by hammering the metal from the inside over a wooden anvil with a flat surface or a concave depression. This technique may also be called sinking[2].

Hollowing using a Hollowing Block (image from D&T Online). File URL: http://wiki.dtonline.org/index.php/Hollowing

The second technique is called raising, in which the vessel is made by hammering on the outside and the metal is placed over a small dome-headed anvil. This method is more difficult, although it also allows more variety and complexity of forms. Another technique is spinning. This can be considered as a mechanical form of raising, as the technique is the same; but a lathe is introduced to force the metal sheet to adopt the shape of the “dome-headed anvil” while both things are spinning (for illustration purposes, find here an online video about this technique). Because the metal is being compressed, there is a possibility that the object will pleat, so a back stick was sometimes used to avoid this. However, early spun work frequently shows some sign of pleating, especially near the rim, so this can be a good indicator of the method used in the manufacturing process. Spun objects also have simple open shapes most of the times (although some closed forms could also be achieved with the use of different chucks)[3].

Another method that also requires a lathe is turning, in which a cast shape is set up in the lathe and any irregularities removed by a sharp tool. This technique may be recognized because the sharp edges of the tool leave small parallel lines on the surface of the final object, unless the metal was very well cleaned up once it was finished. Still, it is important to consider that a burnisher used for spinning might leave a similar trace if it was badly handled. A way to distinguish these two techniques may be by looking at the shape of the object, since turned artifacts are thicker and the metal looks more rigid, whereas a spun object will usually look more even and will have a more gradual shape. For both techniques, the vessel will have a mark of the lathe centre in its base; although turned work may have another centre-mark[4].

In conclusion, we can say that detailed visual observation of artworks can tell us interesting stories about the manufacturing techniques used in an object, as artefacts contain material traces of their own history. Such traces not only inform us about the objects themselves, but they also help us to understand the cultures that produced them and their skills.

[1] Hodges, Henry. 1989. Artifacts. An Introduction to Early Materials and Technology. London: Duckworth, page 73.

[2] Hodges, Henry. 1989. Op.cit., pp. 74-75. Lang, Janet. 2005. “Metals” in Radiography of Cultural Material, edited by Janet Lang and Andrew Middleton, 49-75. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, page 58.

[3] Hodges, Henry. 1989. Op.cit.

[4] Hodges, Henry. 1989. Op.cit.